Abu Abd Allah Mohammed al-Tayyib Ibn Kiran al-Fasi was a senior Maliki, Ashari and Sufi scholar from Morocco. His notable students include Ahmed ibn Ajibah (d. 1809), Ahmad ibn Idris al-Fasi (d. 1837) as well as the Sultan of Morocco, Mawlay Suleiman (d. 1822).

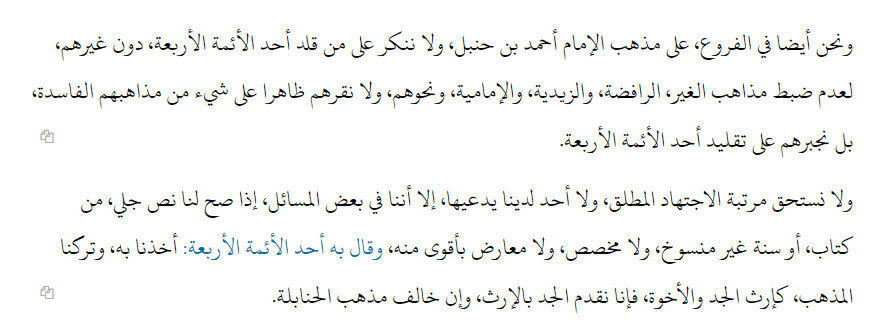

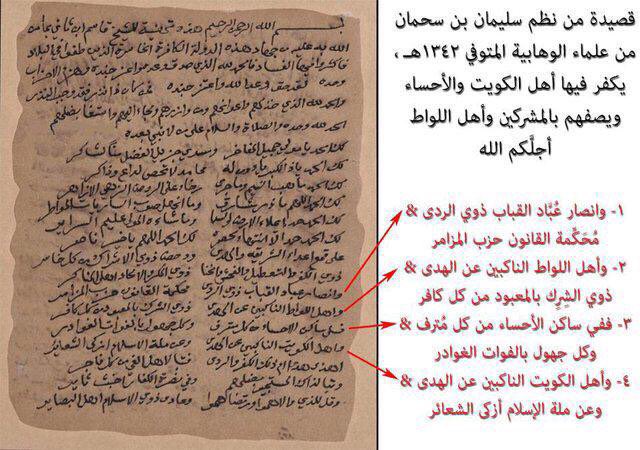

He lived during the same period in which Muhammed Ibn Abdul Wahhab (1703-1792) had founded the Wahhabi movement in Najd. MIAW & his followers had send letters to various Muslim nations inviting them to convert to Wahhabism. As such Ibn Kiran was among those who penned the letter (رسالة السطان مولاي سليمان إلى أمير مكة سعود وشريكه في الحركة) sent by the Sultan of Morocco back to the Wahhabi movement persuading them to disassociate from extremism in takfir and clarifying the creed of Ahlus Sunnah. He had further composed works to refute Wahhabism and to defend the creed of Ahlu Sunnah Wal Jamah.

One of his refutations of Wahhabism is available under the title “رد على مذهب الوهابيين (Response to the Madhab of the Wahhabiyeen)” which can be read in Arabic here.

Unfortunately this work has not been translated to English. However a summary of this work, in a secular style, is available in English within the paper “An Early Response to Wahhabism from Morocco” by Paul L. Heck. It is from this paper that we quote below the summary:

The treatise begins by referring to a group from the East that has troubled the doctrines of Muslims at large (ʿāmmat al-muslimīn), condemning as infidels (takfīr) all those in the umma who oppose their creed.15 This group uses evidence (dalāʾil, i.e. from the texts of revelation) to advance false arguments that charm the faithful, and Sultan Sulaymān has commanded Ibn Kīrān to examine their arguments, especially the points that appeal to people at large, and to refute them where necessary. The point, then, is neither to address the purveyors of Wahhabism in Arabia nor to reject their creed wholesale but rather to manage its effects on the religious arena at home.

Ibn Kīrān first turns to the question of faith. He has to walk a fine line. On the one hand, he has to offer a definition that is broad enough to protect the umma from the condemnations of Wahhabism. On the other, his definition has to speak to the more general concern that Muslims at large do not actually understand the faith. He therefore defines faith quite simply, in the fashion of al-Ghazālī, as trust (tasdīq) in the message of the Prophet Muhammad, but he ties it, in principle, to three conditions: comprehension of the message with no contradiction; conviction in the heart; and submission to the message in life. (Interestingly, Ibn Kīrān cites here “the people of the book” from his own society who, in his view, comprehend the message of Islam and recognize its truth, fulfilling the first and second conditions, but remain infidels for refusing to follow it.)

What, then, would indicate that one is a Muslim? It would require, first of all, the presence of external evidence that one trusts the message of the prophet, namely pronunciation of the two testimonies of faith (i.e. that there is no god but Allah and that Muhammad is Allah’s messenger). It would also require the absence of external evidence that one does not trust (takdhīb) the message of the prophet. Such evidence includes wearing the attire of Jews and Christians, prostrating to the sun and idols, showing disdain for the prophets and the Kaʿba, and throwing the text of the Qur’an in the dirt. Thus, the pronunciation of the two testimonies sufficiently qualifies a person as a Muslim in good standing. Of course, Ibn Kīrān cannot ignore the fact that many Muslims do not perform their religious duties. He

gets around this by speaking of gradations of faith. One who does not perform all that Islam requires is not denied the status of Muslim but rather has failed to reach the perfection of Islam (kamāl al-islām). The details of the faith, while integral to Islam, cannot be equated to faith itself but function, rather, in the way one names something by the things that bring it about (tasmiyat al-shayʾ bi-smi sababihi).

The discussion of faith sets the stage for Ibn Kīrān to address the specific accusations of Wahhabism. This comprises the bulk of the treatise. The goal is to demonstrate that devotional attachment to prophets and saints, including the practice of seeking their intercession to obtain a request, is not tantamount to idolatry (shirk). In this sense, a scholarly discussion of such questions, using Wahhabism as foil, would have served not only the sultan in his attempts to establish his authority over the masters of institutional Sufism but also that of the scholarly class as arbiters of sound piety. Ibn Kīrān performs masterfully. Drawing on the texts of revelation and scholarly consensus, he shows that the various practices associated with the cults of the saints, excesses not withstanding, do not amount to idolatry since they in no way involve the attribution of lordship or divinity to those persons who are the objects of devotional attachment.

He begins his defense by exposing the faulty analogy (qiyās fāsid) at the heart of the claim that devotional attachment is a kind of idolatry. The flaw lies in the conflation of such devotion (taʿalluq) to the worship of idols (ʿibādat al-asnām) against which the Qur’an warns, as if both are a kind of worship of something other than God (ʿibāda li-ghayr allah). The attacks of Wahhabism against the umma are, then, entirely baseless, since they all stem from this faulty analogy. The specific problem lies in the assumption that the verses in the Qur’an that warn against idolatry issue a cause (ʿilla) with universal applicability. Those verses that command worship of God have universal applicability, but those that warn against idolatry, in contrast, apply only to the specifijic situation where people attribute lordship (rubūbiyya) or divinity (ulūhiyya) to the creatures whose assistance is sought. This, Ibn Kīrān admits, is not to deny that some aspects of devotional attachment take on something of the quality of idolatry, but this condition, short of attributing lordship and divinity to the holy persons, is not grounds for takfīr.

At this point, Ibn Kīrān turns to the definition of worship. Prostration alone is not enough to qualify as worship, since that would impute idolatry to the angels who prostrated to Adam and also to Joseph’s brothers and parents who bowed down to him. Notwithstanding Islam’s prohibition of prostration (sujūd) to creatures, worship is not simply the action of abasing and subjugating oneself to another (al-tadhallul wa-l-khudūʿ). In any event, devotional practice in Islam does not include such action. The upshot, Ibn Kīrān concludes, is that the practice of seeking the assistance and intercession of saints is a kind of invocation (duʿā), and here lies the point of confusion. (Recall that al-Albānī recognized invocation of the righteous as a permissible form of mediation.)

Before the coming of Islam, devotional attachment was idolatrous because its practitioners attributed lordship to the objects of their devotional attachment, thinking that the power of their idols to respond to their requests did not depend on God’s favor (ridā allah). This was to make their idols equal to God. In contrast, Muslims who are devoted to holy persons do not think such fijigures can respond to their requests independently of God’s favor. The confusion stems from verses in the Qur’an that deny the efffijicacy of intercession apart from God’s permission and favor. This does not mean that special permission must be received in advance for a holy person to intercede on behalf of others. Why would Abraham have sought forgiveness from God for his father or Muhammad for his uncle? The word for permission (idhn) is to be understood in the same sense as favor (ridā), i.e. the will of God. A holy person can intercede without special permission, but the efffijicacy of his intercession is contingent on God’s will. The requests of Abraham and Muhammad—forgiveness for polytheism—fell short of God’s favor and were therefore not honored by God.

In contrast, the mistake of idolatry is to assume that idols possess the power to honor requests, including requests that do not meet God’s favor, thereby attributing lordship to them apart from God. No one in the umma, Ibn Kīrān affirms, when seeking the intercession of saints or the blessing of their relics, believes that they can honor their requests without God’s favor. Rather, they make the request in the hope that the saints will help them through their invocation and supplication, knowing full well that God will accept their intercession if he wills or reject it if he wills. After all, it is a basic belief in Islam that God is not bound in any way.

Thus, devotional attachment to holy persons actually reflects the deep hope of the umma to be accepted by God along with prophets and saints upon whom his mercies descend. Indeed, the generality of Muslim leaders have encouraged the practice, judging it to be praiseworthy, since the saints constitute gateways to God and God has made it his custom (sunna) to respond to requests through them. Ibn Kīrān mentions a number of scholarly works that approve the practice and detail proper guidelines for shrine visitation. Those who cannot visit the shrines of holy persons should convey their greetings to them, mentioning their needs and wants, for they are the generous masters (al-sādāt al-kirām) who never deny those who look to them as a means to God. This is particularly true in visiting the shrine of the prophet. Those who stand before his grave should feel as if they are standing in his presence during his lifetime. It has long been the consensus of the community that the prophet, whether alive or dead, is attending to the intentions of his followers, and it is impossible for the community to agree on error.

Ibn Kīrān is aware that the “innovator” (al-mubtadiʿ) accepts the intercession of messengers (rusul) when alive but not when they are dead or absent in a distant place. This, he says, is simply a pretext to condemn those who call upon the dead when, as is known, the matter involves something unusual (kharq al-ʿāda), namely the ability of holy persons to hear and comprehend in extraordinary fashion, even in the grave. The innovator knows that God honors the umma with miracles (karāmāt) to its benefit. This in no way makes holy persons divine but gives them access to knowledge of the hidden realm (al-ghayb), access which God grants to whomever he wills.

This is not to overlook the verse in the Qur’an (72:27) that says that God grants access to such knowledge only to a messenger (rasūl) in whom his favor rests. This, however, does not mean that such miracles are limited to the Prophet Muhammad. They also extend to the saints whose rank is not based in themselves but in their association with the light of the prophet. In this sense, the hadith that speaks of the prophets as alive in their graves applies to saints as well. The idea that the power of saints derives from their association with the prophet is central to Ibn Kīrān’s line of thinking throughout the treatise.

Besides, it is a very grave matter to accuse someone of infidelity, tantamount to claiming that they will spend eternity in hell. It makes their life and property licit for the taking, denies them the right to marry a Muslim woman, and deprives them of judgment by the rulings of Islam. The companions taught that it is better to be mistaken in not killing a thousand infidels than to be mistaken in spilling the blood of a single Muslim. Prudence is to prevail above all in matters (masāʾil) such as these where there is ambiguity (shubha) and disagreement (ikhtilāf ) and, moreover, where there is a long-standing consensus of permissibility. A widely acknowledged report says that Adam sought forgiveness from God for his sin through the intercession of Muhammad whose name he saw written on God’s throne alongside God’s own name in the form of the two testimonies. Besides the reports that tell of people asking Muhammad, while alive, to intercede for them with God, there are also many reports of people doing so after his death. Ibn al-Nuʿmān (d. 1284) has recorded these reports in Kitab Misbāh al-Zalām fī l-Mustaghīthīn bi-Khayr al-Anām from which Ibn Kīrān notes one example as narrated by Ahmad al-Qastallānī.16 Doctors had been unable to cure the ailment from which he had long suffered, and so he sought the assistance of Muhammad on the evening of 28 Jumādā al-Awwal 898 ah while in Mecca. During his sleep that night, he saw a man writing on a sheet of paper, “This is the remedy for the ailment of Ahmad al-Qastillānī from [the Prophet].” When he awoke, he had been completely healed by the blessing of Muhammad.

Since the prophet is undeniably a means to a favorable outcome in the next life, his relics are also a source of blessing for the faithful to seek. However, such a practice depends on one’s intention. Since the ignorant masses ( jahalat al-ʿawāmm) do not pursue the practice with a sound intention, undermining its purpose, it is necessary to classify the practice as reprehensible, even if there are plenty of reports that describe the enthusiasm of the companions for things that came into contact with the prophet. Thus, the practice of seeking a blessing from the relics of the saints is also permissible since they have a share in the qualities of the prophet. No less a figure than Ahmad b. Hanbal ruled that there is no harm in kissing the prophet’s grave. Malikism, for its part, judges this action to be reprehensible, but it is impossible to prevent it since it follows from the intense desire of devotees to be in contact with the object of their devotion. After all, Muslims have long been eager to pray in the exact spots where the prophet is known to have prayed, and Muʿāwiya commanded that he be buried with a piece of the prophet’s hair, seeking its blessing, intercession, and mediation. The practice of seeking a blessing via relics has been transmitted from one generation to the next without repudiation. If it were forbidden, the lawgiver would have mentioned it. There have always been scholars who disapproved of the practice, but many others approved it, and some people have trouble setting their hearts on God, which is the goal of Islam, without the mediating assistance of relics.

To be sure, some behavior at shrines is offensive. It is forbidden to circumbulate around the shrine, as the ignorant do, but it is permissible to kiss shrines and rub against them. It is well-known that the delegation of ʿAbd al-Qays kissed the hands and feet of the prophet, and a report in the Sunan of al-Bayhaqī (d. 1066) records that Abū ʿUbayda b. al-Jarrāh kissed the hand of ʿUmar when he went to Damascus. Scholars permit such a sign of deference to those worthy of it. Some scholars permit kissing the graves of saints, copies of the Qur’an, and collections of hadith, and one scholar from Fez says that it is permissible to gather dust from the graves of the saints as a means of healing, claiming that the first Muslims did so with dust from the grave of the martyr-companion Hamza.

Against the innovator’s claim that the first Muslims rejected the practice of uttering invocations at the graves of the righteous, Ibn Kīrān notes that a number of scholars permit invocations at these sites. The status that the inhabitants of these graves enjoy with God makes them sites for the diffusion of divine mercies. Interestingly, here as in other places, Ibn Kīrān defends the practice on the basis of experience (tajriba) in addition to revealed indicant and communal consensus. In other words, if it works, it must be acceptable to God.

One example is a widely accepted story, narrated by two scholars from Morocco. When in Medina, they saw a Bedouin make invocation at the prophet’s grave, saying he had come to seek forgiveness for his sins through the prophet’s intercession. That night while sleeping, one of the scholars saw a vision of the prophet who told him that the Bedouin had been forgiven through his intercession. This should not be surprising since the Qur’an says that God and his angels pray for the prophet, and as noted in a hadith, when one sees the prophet in a dream, it is truly him, since he is the one figure no demon could dissemble. As with previous topics, this practice, since permissible at the prophet’s grave, is also permissible at the graves of saints. There are those who reject this, notably Abū Bakr Ibn al-Arabī (d. 1148), who said that no grave other than the prophet’s is to be visited in order to seek a benefit. But the majority of scholars accept it. To be fair, Ibn al-Arabī may have issued this opinion to close the door to innovations that sometimes accompany the practice of making invocation at shrines, but there is no reason to rely on him alone.

A similar line of reasoning is applied to other practices associated with the cult of the saints. Visitation to the spiritual elite (khawāss al-umma), both living and deceased, is highly recommended. In several hadiths, the prophet states that visiting him after his death is like visiting him when alive, and this, again, extends to the saints. They are entirely united in him, and there is no diffference, save in degree, in the grace ( fadl) to be received from visiting the graves of prophets, saints, and scholars, but it is better to visit the living than the dead since looking into the faces of the righteous is a kind of worship. As al-Ghazali noted (in the chapter of his magnum opus on spiritual companionship), visiting brothers in God is a source of grace. In other words, grace operates via spiritual companionship. The purpose of

the visitation is exposure to the fragrances of divine mercy that are more intense at the graves of the righteous. In this sense, the dead, who are fully in the divine presence, are better able to help the petitioner than the living. To be sure, there are rules. One is not to pray upon graves or to build a mosque over them in the manner of Christians, and shrines should not be a place for congregation with women. Also, out of respect for the body, which enjoys inviolability even after death, one should not sit on the grave, and one should certainly not pray in the direction of graves as people did before the coming of Islam.

As for vows to holy persons in the grave, there is no revealed evidence that treats the subject, making it permissible so long as the purpose is to earn reward for the dead. In this sense, Ibn Kīrān associates the practice to the Fiqh categories of charity (sadaqa) and gift-giving (hiba). For example, a vow to help the poor who gather at the saint’s shrine is a way to benefit the dead (naf ʿ al-mayyit) as a kind of indulgence on their behalf. As a result, scholars generally define the practice as a pious deed (qurba). What is principally at stake is the thing that is vowed to the holy person for his benefit. This is highly commendable, so how can one with no expertise label it idolatry and unbelief ?

The practice of making a sacrifice at the graves of holy persons is more complex. As with vows, the purpose should be charity and not simply the spilling of the animal’s blood, which is counted a pious deed only at the feast of the sacrifice. However, Ibn Kīrān admits, some have a strong desire to spill blood. It is not uncommon to see someone leave the animal after sacrificing it with no indication that they consider it charity. This reflects the customs of the region where many hope to attain the help of the saint in winning over a person of high rank or a tribe. The idea is that it would be a shame (ʿār) for the saint to whom the sacrifice is made to neglect the aspiration of the one who offers the sacrifice. This makes the sacrifice a way to compel the saint to intercede with God. This practice, imposing on the saints the demands of tribal customs that neither revelation nor nature requires is simply empty custom, but there is nothing in it that requires a judgment of idolatry and unbelief.

This is not to ignore the hadith that describes the curses written on the scroll that the prophet kept in the scabbard of his sword, including the curse on those who sacrifice to something other than God. However, as scholars explain, this entails invoking a name other than God’s (bi-smi ghayrihi) when making sacrifice, e.g. the name of an idol, the cross, Jesus, or the Kaʿba, which is not the case when a Muslim sacrifices to a saint. Only the name of God is mentioned. Scholars do teach that the meat of these sacrifices is not to be eaten, but the one who makes the sacrifice is still a Muslim unless he elevates to the level of lordship the one to whom he sacrifices. Islam recognizes sacrifices that are not made to God, such as sacrifices made to welcome someone—a sultan or newborn. No one thinks this is forbidden. It is only when a sacrifice is made in a name other than that of God that it becomes apostasy. Even then, there is always opportunity to

repent.

Wahhabism, Ibn Kīrān avows, has upset the umma by propagating its creed through the texts of revelation, but there is nothing there to support their claims, especially the charge that those verses in the Qur’an that condemn the worship of something short of God (dūn allah) apply to devotional attachments to prophets and saints, since, in point of fact, no attribution of lordship or divinity accompanies these attachments. Indeed, some scholars permit the building of domes (but not mosques) over the graves of the righteous, covering them in silk cloth, and lighting candles in the vicinity. All of this facilitates the benefit people gain from visiting the saints, for it prevents the shrines from falling into disappear. Other nations allowed the shrines of their prophets to disappear without a trace, and this led to their own demise. (Presumably, a nation’s sustainability depends on its devotion to its pious ancestors.) In this sense, Wahhabism has made a grievous mistake in condemning tawassul through the community’s holy persons. Indeed, the practice is a sign of human reliance on the grace of God ( fadl allah) that works through the special causality (tasabbub) of those God has honored. This is a sign of faith, which should not be confused with those who insult the prophet, make alcohol permissible, and require others to prostrate before them. After all, one can only be condemned for manifest signs of apostasy. Ibn Kīrān ends by quoting the innovator’s claim that those deficient in the basics of Islam are no longer Muslim. Alas, our authority responds, the innovator has failed to see that faith is faith even if partial.